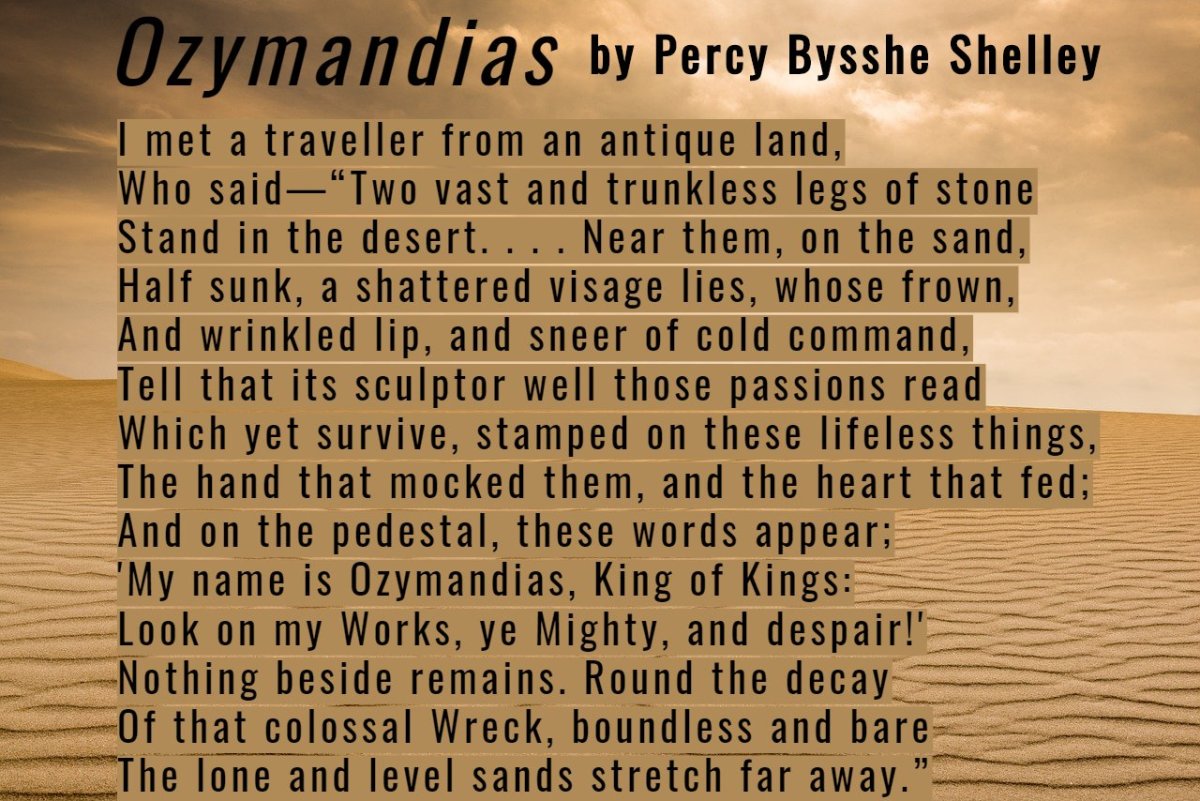

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!" The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed: Which yet survive (stamped on these lifeless things) Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Half-sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,Īnd wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Who said – 'Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Here, the sculptor outlives the pharaoh, at least until nature reclaims the last vestiges of masonry, and these, too, are dissolved to sand. Russian poets used to have a saying that the poet outlives the tsar. If there is little left of the sculptor's work, there is enough, so far, to bear witness to tyranny.

#Ozymandias percy bysshe shelley full

The full irony of this is brought home by the final image of the boundless sands, stretching as far as the eye can see. There is a third character, of course: the sculptor who, it seems, has revealed his master's true nature, and, moreover, must be responsible for the telling second half of the inscription: "Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!" The "wrinkled lip" is a particularly brilliant detail that suggests an age of sneering and sensuality in its possessor. Shelley has created a monster, it seems, out of his own revulsion from tyranny. He seems to have had little facial resemblance to the benign, serenely smiling pharaoh familiar to visitors to the British Museum.

Shelley's free, "romantic" way with the sonnet-form – the unusual pattern of the rhymes, and the presence of half-rhymes – is wholly appropriate.Īnother character in the poem is Ozymandias himself, his whole personality summed up in a few strokes. His tale is strongly pictorial, and moves with the fluency and drive of recollection. Virtually all the sonnet is spoken by the traveller.

First, he sets a fictional scene, introducing a second character, a kind of Ancient Mariner, though one with the gift of brevity, to give his "personal account" of the ruined sculpture. Whether a writer is drawing on personal experience or literary research, imagination is crucial, and Shelley approaches the task with great imaginative flair. As potently as the wilderness symbolised spiritual freedom for the Romantic writers, ancient ruins declared the triumph of time and nature over human tyranny.Ī competition, light-heartedly undertaken, may have been the sonnet's immediate occasion, but Shelley's passion for the politics of his theme is evident in the poem and integral to its solidity. "The book was central to the evolution of Romanticism from a specifically English and insular aesthetic to a universal political and philosophical force," writes the anonymous author. The various literary sources of the poem are fascinatingly explored in this essay which suggests that Volney's The Ruins of Empires (a French work appearing in English translation in 1792) was of major significance, and not only to Ozymandias. Shelley could not have seen it at the time of writing, and he had never been to Egypt, but he would have certainly seen illustrations of ruined cities and statues. This head would later be shipped to the British Museum. Shelley's interest in Egyptology was already established, as revealed by some of the imagery of an earlier poem, Alastor, but perhaps it had been rekindled in part by the news of the excavation of the colossal head of Rameses II.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)